To All,

(A interesting aside is that the King James version of Rev.18:12 says that "thyine wood" will be one of the products that is no longer sold after the fall of Babylon. Thyine wood is a synonym for the wood of the Barbary arborvitae.)

Recall that "naranja" is the word for orange in Spanish. Also, there is no word for orange in Greek or Latin since this fruit was not known in classical times.

The four eng- ineers Wore orange brassieres.

When you peel a navel orange, you see a funny little growth at the end opposite the stem, i.e., at the same end as the navel. This growth is a quirk of the mutation that created the navel orange, and it has been inherited in all navel oranges. It is a secondary fruit, a sort of runt twin of the main fruit, with its own set of tiny segments. The pictures below show this underdeveloped twin fruit. (The first four pictures are of the same orange, the fifth is from a different orange, the sixth is from yet another orange, and the last picture, which is the only one not taken by me, is from the Internet.)

Use of Orange Peel in Perfume

Do you want a radiant complexion? Then don't throw those orange peels in the trash, say the skin experts. Join the do-it-yourself cosmetics crowd and take advantage of the nutrients in orange peels by grinding them to a powder, adding milk or yogurt to form a paste, and applying the mixture to your face to make a mask. Advantages include banishing acne, whitening your skin, removing blackheads, reducing wrinkles, and exfoliating and toning your skin. Caution! Be sure to use organic oranges so that you do not apply pesticides to your face. For instruction, onevideo is best on making the orange powder and another video is best on making the paste and applying the mask. Orange peel is also used as a slug repellent.

Etymology of Citrus

The place to start for the etymology of citrus is with the on-line Oxford English Dictionary (OED):

Etymology: < classical Latin citrus, denoting an African tree, probably Tetraclinis articulata, in post-classical Latin also denoting the citron tree, Citrus medica (5th cent.), further etymology uncertain and disputed: probably either < ancient Greekκέδρος, perhaps via an Etruscan form, or borrowed, together with the Greek word, from another (unidentified) language.

My interpretation of this passage is that in classical Latin, i.e., in the last few hundred years B.C., citrus was the name of the tree that is now sometimes called the Barbary arborvitae (Tetraclinis articulata). This tree is not related to the citrus fruits. This tree was well-known in ancient times since its wood was valued for decorative woodwork and for its scent. It is closely related to the arborvitae shrub that is common in New England. In fact, arborvitae fringes my parking lot. If you are familiar with our local arborvitae, then you can see its close relationship to the Barbary arborvitae. Here are some pictures. The first two, high quality pictures, are from the Internet; I took the rest on 25 Mar 2015.

- The Barbary arborvitae.

- The arborvitae found in New England.

- A panoramic shot of my parking lot showing the arborvitae at its edge. My car provides scale.

- A medium-range shot of my arborvitae.

- A close-up of the arborvitae.

- A close-up of a single branch. You can tell that I am a rookie hand model since I let my watch show in the picture.

A few hundred years passed, language evolved, and in post-classical Latin, perhaps around the fifth century A.D., the word citrus was transferred to the citron, which is a true Citrus and was the first citrus fruit to become known to the West (see e-mail of 14 Mar 2015). It is not clear why this transfer of meaning occurred, but it is suggested that the reason might be that the wood of the two trees is similar. Another millenium passed, and in 1753 Linnaeus picked Citrus as the official name of this genus. Therefore, we now call these fruits "citrus fruits."

(The paragraph above from the on-line OED is much more informative than what is provided in my hard-copy OED. (In the 1970s I bought the two-volume micro-print edition cheap since the cover of one of the volumes was upside-down.) This shows that even the OED makes progress. Thanks to Latinist David Warrington for helping me with the etymology of "citrus." In particular, he has access to the on-line OED, which I don't.)

Etymology of Orange

Wikipedia says that "orange" was applied first to the fruit in the 13th century, which is soon after the fruit first made it to the West, and later applied to the color in the 16th century. Before the fruit became known, the color was called yellow-red or some variation on that. If you insist on a full etymology, chew on this offering from Wikipedia:

The word ultimately derives from a Dravidian language—possibly Telugu నారింజ nāriṃja or Malayalam നാരങ്ങ nāraŋŋa or Tamilநாரம் nāram—via Sanskrit नारङ्ग nāraṅgaḥ "orange tree", with borrowings through Persian نارنگ nārang and Arabic نارنج nāranj.[2] The initial n was lost through rebracketing.

Recall that "naranja" is the word for orange in Spanish. Also, there is no word for orange in Greek or Latin since this fruit was not known in classical times.

Rhymes with Orange

What about the age-old challenge to budding poets to come up with a rhyme for "orange"? Something called the Oxford Dictionaries, which clearly tries to blur the distinction between itself and the OED, says:

Orange has almost no perfect rhymes. The only word in the 20-volume historical Oxford English Dictionary that rhymes with orange is sporange, a very rare alternative form of sporangium (a botanical term for a part of a fern or similar plant).

(Not only is "sporange" such a trick word that it doesn't count, but, as I would pronounce it, it is not an exact rhyme. This latter opinion is seconded by Wikipedia.) Nevertheless, word artists are always coming up with off-brand rhymes. Typical of this horseplay is a poem by Willard Espy:

Another example is provided by the rapper Eminem:

"People say that the word orange doesn't rhyme with anything ... I can think of a lot of things that rhyme with orange," said Eminem, seated behind a mixing board at his private recording studio, before effortlessly conjuring an on the spot rap about putting an "orange, four-inch, door hinge in storage" and having "porridge with Geo-rge."

The Oxford Dictionaries gives various near-rhymes such as challenge and scavenge. I have a vague memory of Ira Gershwin working a clever rhyme for orange into some song (or maybe lamenting that there was no such rhyme), but I can't find this line. Perhaps a reader can supply it.

Propagation of Seedless Citrus Fruits

In nature citrus trees propagate by seeds rather than by underground shoots, plantlets, or any of the other methods of vegetative propagation that are frequently used by other plants. For concreteness, consider the seedless orange. The ubiquity of seedless oranges in grocery stores proves that they are propagated with great success, but, since they have no seeds, they cannot be propagated in the natural citrus manner. This leaves us with a huge question: How are seedless oranges propagated without seeds? The answer is that seedless oranges are propagated by grafting. (For the principles of grafting and its terminology, see the e-mail on apricots of 1 Feb 2015.) That is, once you have developed a seedless orange, perhaps by a breeding program or by stumbling on one that has occurred naturally, you must take a twig from the seedless orange tree and graft it onto a suitable rootstock to propagate it. In short, we have massive use of grafting to thank for our seedless fruits, which add so much pleasure to our eating.

In particular, navel oranges, which are seedless, are propagated solely by grafting. This means that selective breeding cannot be practiced on navel oranges. Moreover, apart from the mutations that have occurred, all of the navel oranges are clones of the first navel orange discovered as a mutant some two centuries ago in Brazil. (I don't want to get into details, but navel oranges produce very little pollen and are also self-incompatible, which means that a navel orange cannot be successfully fertilized by itself (or by a very close relative); if unfertilized, they do not produce seed. Since navel oranges are also parthenocarpic, which means that they produce fruit even if unfertilized, the result is that pure groves of navel oranges will produce fruit but not seed. Moreover, the oranges are all clones since no sexual recombination takes place.) (Keep in mind that, despite what some say, not all navel oranges are genetically identical since mutations do occur; for example, the cara cara navel orange (8 Feb 2015) originated as a mutation of the standard navel orange.) (Pedantic note: There is a minor exception to the statement that all navel oranges are descendants of the first navel orange that originated in Brazil. The mutation that originally produced the navel orange occurred a second time, with this second occurrence affecting a blood orange and resulting in what is called the scarlet navel orange.)

You will not be surprised to hear that a process as important as grafting has been celebrated in fine art. Below is Grafting, an 1870 wood engraving from a drawing by Winslow Homer (see initials in lower left). Note the numerous grafts on the same rootstock. This engraving is now held by the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art but is not on view. Prints can be purchased starting at $44.99.

We should not ignore the dangers of the lack of genetic diversity of the cloned, seedless fruits. Wikipedia gives the banana as an example of this danger:

One disadvantage of most seedless crops is a significant reduction in the amount of genetic diversity in the species. As genetically identical clones, a pest or disease that affects one individual is likely to be capable of affecting every clone of that individual. For example, the vast majority of commercially produced bananas are cloned from a single source, the Cavendish cultivar, and those plants are currently threatened worldwide by a newly discovered fungal disease to which they are highly susceptible.

Rootstocks Used with Oranges

Oranges are grafted on a number of rootstocks, where the rootstock chosen depends on climatic conditions, soil conditions, and the prevalent diseases that need to be dealt with. The sour orange (17 July 2014) has been found overall to be the most important rootstock, with other popular rootstocks being the rough lemon and the trifoliate orange. In addition, the rootstock influences the physical and chemical attributes of the fruit. For example, Valencia oranges on sour orange stock have been found to have more dry matter in the peel, pulp and juice than those on rough lemon. This entire paragraph is taken from an authority that you can consult for much more information about orange rootstocks.

The Funny Little Growth Inside a Navel Orange

- A California navel orange peeled and broken in two. You can see the secondary fruit at the bottom of the portion on the right.

- The secondary fruit has been dissected out so you can see it separated from the main fruit.

- A close-up of the secondary fruit.

- A close-up of the secondary fruit with the segments somewhat separated so you can see them better.

- A close up of the secondary fruit from a cara cara navel orange with the segments somewhat separated.

- A sideways cross-section of a navel orange near the navel end. You can see the segments of the main fruit surrounding the segments of the secondary fruit.

- A navel orange cut lengthwise in half so you can see the main fruit and the secondary fruit in longitudinal cross-section.

I have determined through experiment that sometimes the secondary fruit is good to eat and sometimes it is inedible. I have found that there is considerable variation in the size of the secondary fruit, even within oranges bought at the same time that externally look identical.

Curaçao

Wikipedia describes the citrus basis of the liqueur Curaçao:

Curaçao (/ˈkjʊərəsaʊ/ kewr-ə-sow) is a liqueur flavored with the dried peel of the laraha citrus fruit, grown on the island of Curaçao. A non-native plant similar to an orange, the laraha developed from the sweet Valencia orange transplanted by Spanish explorers. The nutrient-poor soil and arid climate of Curaçao proved unsuitable to Valencia cultivation, resulting in small, bitter fruit of the trees. Although the bitter flesh of the Laraha is all but inedible, the peels are aromatic and flavorful, maintaining much of the essence of the Valencia orange.

Watch Out for Small Sample Bias

I have often cautioned my readers that they should not put too much weight on the Fruit Explorer reports based on just one or two fruits. That is, there is variation in fruits, as in everything else, and the one or two that I tried might have by chance been exceptionally good or bad, which means that my reports cannot be taken to be reliable indicators of what the fruit is typically like. Here is an illustration of this. Dave Robinson wrote on 26 Jan 2015, the day after my e-mail on the satsuma tangerine: "...earlier on the day your Fruit Explorer e-mail arrived I had bought some satsumas. Gwenie and I had them this morning and judged them inferior. We have had many in the past and some are wonderful. Citrus is hard to predict."

Use of Radiation to Generate New Varieties of Grapefruit

Rather than wait for mutations that might improve a fruit, scientists can speed up the evolutionary process by using mutagens to induce mutation. (A mutagen is something that causes mutations to happen at an elevated rate, e.g., x-rays, cigarette smoke, asbestos.) .Wikipedia points out how radiation is used to produce mutations in the hope of producing a better grapefruit.

The 1929 Ruby Red patent was associated with real commercial success, which came after the discovery of a red grapefruit growing on a pink variety. The Red grapefruit, starting with the Ruby Red, has even become a symbolic fruit of Texas, where white "inferior" grapefruit were eliminated and only red grapefruit were grown for decades. Using radiation to trigger mutations, new varieties were developed to retain the red tones which typically faded to pink; the Rio Red variety is the current (2007) Texas grapefruit with registered trademarks Rio Star and Ruby-Sweet, also sometimes promoted as "Reddest" and "Texas Choice". The Rio Red is a mutation bred variety which was developed by treatment of bud sticks with thermal neutrons. Its improved attributes of mutant variety are fruit and juice color, deeper red, and wide adaptation. [Footnotes deleted. Also, punctuation corrected to eliminate a run-on sentence; when it comes to editing, I guess you get what you pay for.]

You might want to take a look at the Mutant Variety Database kept by the International Atomic Energy Agency.

The Orange Blossom

Wikipedia provides information on orange blossoms.

- The orange blossom is the state flower of Florida.

- Orange blossom is highly fragrant and is an important ingredient in some perfumes.

- Honey that bees make when working orange blossoms has a very orangey taste and is highly prized.

The classic bluegrass fiddle tune is "The Orange Blossom Special." Here is a nice short version by Flatt and Scruggs. You might prefer a longer, live version by the Charlie Daniels Band. If your taste is more refined, you might prefer Steve Martin doing a medley of "The Orange Blossom Special" and a bluegrass version of "King Tut."

Too Much Fun

I have discovered that it is possible for an orange to be too good. I chomped down on a segment of navel orange that proved to be exceptionally juicy. The fountain of juice caught me by surprise, went down the wrong way, started me coughing, and forced me to stop eating for two minutes.

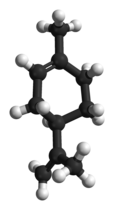

Orange peel is a workhorse ingredient in perfumes. Wikipedia says that the active ingredient is a compound called limonene, which smells strongly of oranges. The structure of limonene is pictured below in both a line drawing and also a ball-and-stick drawing. At Christmas, perfume and beautify your home with an orange peel garland. Note the orange peel garland draped on an arborvitae.

The article in Wikipedia allowed me to take a giant step forward in my knowledge of perfume. It turns out that the world's first recorded chemist was from the second millenium B.C. in Mesopotamia and was a perfume-maker. Wikipedia also tells us:

The conventional application of pure perfume (parfum extrait) in Western cultures is at pulse points, such as behind the ears, the nape of the neck, and the insides of wrists, elbows and knees, so that the pulse point will warm the perfume and release fragrance continuously.This article also brings out the importance of plants in perfumes.

Plants have long been used in perfumery as a source of essential oils and aroma compounds. These aromatics are usually secondary metabolites produced by plants as protection against herbivores, infections, as well as to attract pollinators. Plants are by far the largest source of fragrant compounds used in perfumery. The sources of these compounds may be derived from various parts of a plant. A plant can offer more than one source of aromatics, for instance the aerial portions and seeds of coriander have remarkably different odors from each other. Orange leaves, blossoms, and fruit zest are the respective sources of petitgrain, neroli, and orange oils.

Just as we have insects to thank for flowers (since the purpose of showy flowers is to draw the attention of pollinators), this passage brings out that we have herbivores (largely insects) to thank for perfume. (Similarly, we have herbivores, largely insects, to thank for spices, which are typically also a defense against herbivores. Flowers, perfumes, spices--Face it, insects are our benefactors. And this is not even mentioning pollination, which is the basis of our civilization.) There's lots more material, but since I am not the perfume explorer, I will get back to the topic.

Skin Health Through Orange Peel Beauty Masks

Party Reminiscence

Rather than a party tip, I will give a party reminiscence. At a party in the 1970s, a word question came up, and the host pulled out the OED. We hunched over it to research the question. A latecomer entered the room and remarked, "You know it's a wild party when you walk in and find people looking things up in the OED." [Note to Dave and Gwenie: The latecomer was Doug Peine.]

Rick

P.S. This is the fiftieth Fruit Explorer e-mail.